Richard Dadd

1817-1886

On several pages scattered across the 'Net, one can find this passage:

-

Richard

Dadd was an English artist of the late nineteenth century, known for his

fantastic subjects. He went mad.

This seems to be the sum total of the common view of the Victorian painter Richard Dadd, and it does not do him justice. Today, he is known chiefly for a few tremendously evocative fairy paintings, including The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke, (which occasioned a song by Queen), and for having murdered his father. Yet Dadd was held to be a painter of great talent in his own time, has since demonstrated his status as a minor Victorian master, and is one of the most intrinsically interesting painters of the last two hundred years, in large part because of the unique features of his work.

Although there are a number of sites on the Web that mention Dadd in one context or another, none offers a view of Dadd the historical figure and Victorian painter. This site exists for that purpose.

Dadd The Historical Figure

Richard Dadd was born, the fourth of seven children, to Robert and and Mary Ann Dadd, in the town of Chatham, in Kent, on August 1, 1817.As a child, Richard attended The King's School at Rochester, where he developed a taste for classics and Shakespeare that stayed with him throughout his life. Although little of his work from this period survives, Allderidge has him sketching seriously at 13.

In 1834, when Dadd was eighteen, his family moved to Suffolk Street, Pall Mall, in London, and Richard's father took up work as a carver and bronzeworker in the near-by Haymarket. Robert Dadd's work put his family in contact with contemporary artists and art patrons, and Richard may have received informal tutorials from some of his father's associates before he applied and was admitted to the Royal Academy in December of 1837 at age 20.

At the Academy, Dadd became friends with John Phillip, who was subsequently to marry Richard's sister Mary Elizabeth, and William Powell Frith (1819-1909), who was subsequently to play a significant role in Victorian genre painting and sontemporary social documentation. Later, this circle was expanded to include Augustus Egg, Harry Nelson O'Neill, Alfred Elmore, Edward Matthew Ward, Thomas Joy and William Bell Scott. This group was, in one form or another, known as the Clique in contemporary artistic circles, and frequently met in Dadd's rooms in Great Queen Street.

While at the Academy, Dadd won three silver medals for draughtmanship, and began exhibiting during his first year at the Academy, in the British Artists' Association. During 1840 and 1841, he bagn to work on Shakespeare illustrations in earnest, and in 1842, he exhibited a version of one of his greatest early works, Come Unto These Yellow Sands at the Royal Academy Exhibit.

That same year, he received a commission to provide illustrations for Samuel Carter Hall's Book of British Ballads (London: Jeremiah How/Vizetelly Brothers and Co.), which he executed on woodblocks. At roughly the same time, he undertook to decorate the interior of 26 Grosvenor Square for Lord Foley with scenes from Tasso and Byron.

In July of 1842, Richard accompanied his patron, Sir Thomas Phillips, on an extended Grand Tour of Europe and the Middle East. They crossed from Dover to Ostend on July 16, and within the first month had visited the Rhine Valley, Lake Maggiore, the Bernese Alps, Venice (where Dadd spent time studying Veronese and Tintoretto), Bologna and Alcone. From Alcona, the two sailed via Corfu to Patras and on to Athens. From Athens, they visited Smyrna and Constantinople, returning to Symrna in late September of 1842. There, Phillips received a brief from the British ambassador to Turkey to visit the Castle of St. Peter in Bodrum, which he and Dadd did, apparently with a view to beginning negotiations for the purchase of the marbles from the tomb of Mausolus there.

Portrait of Sir Thomas Phillips in Eastern Costume, Reclining (1842)

From Bodrum, Dadd and Phillips moved on to Lycia in Asia Minor, and then to Rhodes, Cyprus and Beirut. From Beirut, they travelled by mule and foot to Tripoli and Damascus, followed by a swift tour of Holy Land sites that left them, exhausted, in Jerusalem, in early November of 1842. After an excursion to the Dead Sea, the two traveled by boat up the Nile valley to Thebes, arriving there just before Christmas. During this period of the trip, Dadd began to experience headaches and "sun stroke."

Dadd and Phillips traveled back down the Nile to Alexandria at the end of December. From Alexandria, the two men sailed to Malta and then on to the west coast of Italy, where Dadd began suffering from various kinds of more or less paranoid delusions of pursuit, and became increasingly violent toward Phillips. In Rome, Dadd experienced an incontrollable urge to attack the Pope during one of his public appearances, and by the time the two reached Paris in April or May of 1843, Dadd's symptoms became so acute that Phillips was no longer able to explain Dadd's behavior as exhaustion or sunstroke. Dadd left Phillips in Paris in late May, and returned to London.

Dadd's later commentary on this period of his life is instructive:

|

On my return from travel, I was roused to a consideration of subjects which I had previously never dreamed of, or thought about, connected with self; and I had such ideas that, had I spoken of them openly, I must, if answered in the world's fashion, have been told I was unreasonable. I concealed, of course, these secret admonitions. I knew not whence they came, although I could not question their propriety, nor could I separate myself from what appeared my fate. My religious opinions varied and do vary from the vulgar; I was inclined to fall in with the views of the ancients, and to regard the substitution of modern ideas thereon as not for the better. These and the like, coupled with an idea of a descent from the Egyptian god Osiris..." (quoted in Allderidge, pp22-3). |

| Walpurgis Night, The Piper of Neisse, The Devil's Bridge (1842) |

Dadd was suffering, we are now told, from a manic-depressive or bipolar disorder. It seems obvious from the self-descriptions that have come down to us from the period just before and after the murder of his father that the precipitating event in Dadd's mental life occured in Egypt, probably in the Nile Valley, when he first encountered images of Osiris. His descriptions of being prompted by voices are entirely consistent with other roughly contemporary accounts of psychosis (one thinks of Gregory Bateson's Perceval's Narrative while reading many of Dadd's descriptions) and indeed with the Victorian pattern of psychoses involved divine election/questing of the sufferer.

Essentially, Dadd had become convinced that he was being called upon by divine forces (usually Osiris) to do battle with the Devil, who could assume any shape he desired and was incarnate all around him. Plagued by this fixation, Dadd continued working and living in Newman Street, where he subsisted largely on hard-boiled eggs and ale. Dadd's brother George was at this time also showing signs of mental illness, and Richard's father, although maintaining publicly that nothing was wrong with Richard, had Alexander Sutherland of St. Luke's Hospital examine Richard: Sutherland concluded that Dadd was non compos mentis.

In spite of this diagnosis, Robert Dadd accompanied Richard on a trip to Cobham on August 28, 1843, during which Richard had promised to "disburden his mind" to his father. The two traveled down to Cobham, ate dinner in a local inn, and then walked out into the countryside. At abut 11:00 PM, near a chalk pit called the Paddock Hole, Dadd attacked his father with a knife and razor, and killed him.

Richard left Cobham immediately after killing his father, heading to Dover, where he boarded a ship for Calais.

Robert Dadd's body was discovered on Tuesday morning, and the police were called in. There is some indication that they feared Richard Dadd dead as well: they searched for Richard in the Cobham area. When Richard's brother arrived at the crime scene, he immediately assumed Richard had killed his father, and Richard's description was sent to the Metropolitan Police. Dadd's rooms in Newman Street where searched, and the eggs and ale fetish was discovered, along with sketches of Richard's friends and associates, each with a slashed throat.

Meanwhile, Richard had been detained in Calais by the douaniere, released and left to change his bloodstained clothes in an inn in Calais. From Calais, he travelled to Paris, during which trip he attempted to cut the throat of a fellow traveler. He was taken into custody in Montereau, where he identified himself as Richard Dadd and confessed that he had murdered his father. From Montereau, he was moved to the Clermont asylum at Fontainebleau, where a search of his person revealed a list of people "who must die": his father's name was at the top of the list.

Dadd remained in Clermont until late July of 1844, when he was returned to England for a hearing in Rochester. Dadd pled guilty and was sentenced to removal "to a place of permanent safety without coming to trial" (Greysmith, pp. 62). Dadd's twenty-seventh birthday had just passed.

That place was Bethlem Hospital's crimimal lunatic department: the hospital that gave bedlam its origin and resonance. Dadd was to remain in Bethlem Hospital until July of 1864: a period just under 20 years. Here he did his most remarkable work, including The Fair Feller's Master-Stroke, Contradiction. Oberon and Titania, and Portrait of a Young Man. William Michael Rossetti, the brother of the poet Christina Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelite founder Dante Gabriel Rossetti, visited Bethlem during this period and recorded his impressions of Dadd at this time:

-

I saw the ill-starred painter who was sitting with two or three others

in a large airy room, having beside him a mug of beer or some other refreshment.

His aspect was in no way impressive or peculiar, he seemed perfectly composed,

but with an undercurrent of sullenness.

Sketch to Illustrate the Passions: Agony -- Raving Madness (1854)

In July of 1864, perhaps because Bedlam was overcrowded, Dadd was moved to a new lunatic asylum at Broadmoor, outside London. Here he remained, painting constantly and receiving infrequent visitors until January 7, 1886, when Richard Dadd died, "from an extensive disease of the lungs."

Dadd The Painter and Illustrator

I am not competent to evaluate Dadd's work, except to say that (a) it infuriates me that people refer to Dadd as a "fairy painter" (something a review of his canon would never sustain, on a count alone) and (b) I never tire of looking at his paintings.

Dadd's work does seem to be unfamiliar to most writers on Victorian art. Julian Treuherz's summary of Dadd in his Victorian Painting seems a fairish example of the typical position on Dadd's contributions to the canon:

-

...in the early

40s, [Dadd] exhibited subjects from A Midsummer Night's Dream and The

Tempest, noteworthy for their delicacy of touch and supernatural lighting

effects....[After his detention]Dadd was extremely fortunate in being

attended by sympathetic doctors who encouraged him to paint. Isolated

form the world outside and from new developments in art, he fell back

on the themes of his sane period, historical and literary subjects, recollections

of the Middle East, portraits and fairies. The body of work he produced

after he went mad is often bizarre and puzzling, but even in his disturbed

state he painted with a clarity of form which reflects Nazarene influence....[his]

most extraordinary achievement is the enigmatic The Fair Feller's Master-Stroke

(1855-64), a hallucinatory vision of fantastic creatures, seen as if with

a magnifying glass through a delicate network of grasses and flowers...(Treuherz,

pp. 54-55).

In fact, Dadd had been a public artist exhibiting his work to a (potentially paying) populace through authorized viewpoints like the Royal Academy for only a few years; his work is the work of a private artist, someone compelled to paint. The fact that his private work was done in a context that did not allow him to circulate among his peers has been overstated -- for example, when Dadd was visited by a journalist at Broadmoor in 1877, Dadd exhibited familiarity with the current art scene, including the paintings which had been exhibited the previous year at the annual Royal Academy Exhibit. What sets Dadd apart as a painter, and as an historical figure, is the extent to which he was his own painter: unlike most of the more well-known Victorian painters, who were constantly struggling to reconcile their artistic intentions with commercial success, Dadd painted, for most of his mature career, precisely what he wanted to paint.

I wrote, "what he wanted to paint" but perhaps I should say what he was compelled to paint. Reviewing his work in either Allderidge or Greysmith, any sensitive viewer is immediately struck by several recurring features of Dadd's work that are not "bizarre and puzzling" but suggestive of strong compulsions.

Crazy Jane -- detail (1885).

Dadd painted for himself. He had no audience, no following, no patrons, and very little in the way of intellectual community (most people at Broadmoor could not read or write for much of his time there) for most of his adult life, yet he made art regularly and well throughout that period. Ultimately, what Dadd's work offers us, in addition to the pleasure of viewing the work of a good painter and illustrator, is an unparalleled body of work that provides insight into the need at the heart of art itself.

Dadd In Contemporary Culture

The Tate (possibly the world's greatest museum) has an article in the latest issue of its TATE ETC magazine on Orientalist painting (that peculiar Victorian imperialist vice), and Dadd figures in the piece. Links are included to the Dadd pieces in the Tate collections.

I don't know quite what this BBC-hosted thing on Richad Dadd is, but I dig it.

Dadd's fairy paintings in the context of the Victorian fairy painting subgenre.

Dadd gets blog'd: a serious-minded blog entry on Dadd.

Dadd has made it to Wikipedia, which is I suppose a kind of Internet canonization.

His paintings and drawings still appear on the market from time to time.

You can actually buy a fewDadd prints from AllPosters.Com.

Neil Gaiman, the creator of the Sandman comic, is apparently a Dadd fan.

Dadd Paintings, Drawings and Illustrations On The Web

The Closet Scene From Hamlet (1840: oil on canvas)

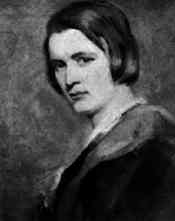

Portrait of the Artist (1841?: oil on panel)

Minaret of the Grand Mosque, Damascus (oil)

Jerusalem from the House of Herod (watercolor)

Puck (1841: oil on canvas).

Titania Sleeping (1841: oil on canvas)

Portrait of Sir Thomas Phillips in Eastern Costume, Reclining (1842: watercolor)

Walpurgis Night, The Piper of Neisse, The Devil's Bridge (1842: ink)

Come Unto These Yellow Sands (1843: oil on canvas)

Caravan Halted By The Sea Shore (1843: oil on canvas)

Portrait of a Young Man / Dr. Charles Hood (1853: oil on canvas)

Sketch to Illustrate the Passions: Love, Agony -- Raving Madness, Melancholia, and Senility (courtesy of Sim Fine Art).

Contradiction: Oberon and Titania (1854-8: oil on canvas) -- arguably superior to the FFMS.

Crazy Jane (1855: watercolor) -- a marvelous work, with (as someone pointed out to me) a man as Dadd's model

The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke (1855-64: oil on canvas) and the painting with Dadd's poetic explication thereof. If you are ever in the Tate in London, and they have FFMS out, don't miss it.

Works On or Mentioning Dadd

-

Allderidge,

Patricia. The Late Richard Dadd: 1817-1886 London: The Tate

Gallery [n.d.] By

far the best book for a view of Dadd's work.

Allderidge, Patricia. Richard Dadd. London: Academy Editions, 1974.

De Saint Pierre, Isaure. Richard Dadd - His Journals Ellis. 1984.

Greysmith, Richard. Richard Dadd: The Rock and Castle of Seclusion: London: Studio Vista, 1973. The most sensitive and coherent of the Dadd biographies.

MacGregor, J.M. The Discovery of the Art of the Insane. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Treuherz, Julian. Victorian Painting. London: Thames and Hudson, 1994.

Last updated 5-24-07 by Marc Demarest (marc@noumenal.com)