The Responsible Preparation of Electronic Literary Texts

Marc Demarest

marc@noumenal.com

June 1997

The best text of The Great Gatsby is found in Fitzgerald’s posthumous Three Novels. Of the seventy-five significant changes between the first edition and the latter text, thirty-eight were suggested by Fitzgerald, the rest being inserted by the publisher without [Fitzgerald’s] authorization and, conversely, a number of other corrections which the author proposed were not made. Thus, even the "best" text does not represent the way Fitzgerald wanted his book to read.

Richard D. Altick, The Art of Literary Research (1981).

P-Texts: The Book As An Historical Artifact

To begin, some facts about some famous printed texts (p-texts):- More than 30% of the material in the Bonchurch edition of the Collected Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne are forgeries, committed by Swinburne’s executor, T.J. Wise, and added to the Collected Works as original, unpublished Swinburne material.

- There are four different texts of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, all in circulation today.

- In the first American edition of Henry James’ novel The Ambassadors, Chapters 28 and 29 are reversed.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne intended all editions of his novel The Scarlet Letter to be published with a prefatory tale called "The Custom-House." More than 25% of the trade paperback editions of The Scarlet Letter in circulation today do not include this story, which provides the key to the interpretation of the novel.

All of these factoids go toward pointing out that texts, despite their calm, ordered appearance, are problematic: complex, multifairous products of a complex socio-historical context.

Printed texts (p-texts) are more than convenient (if now antiquated) containers for text; they are historical artifacts, and much of their significance derives not from the text within them, but from the container itself: the typography, the binding, the material inserted by the publisher before and after the text itself, the dust-wrapper, the marginalia of previous owners.

P-texts have an origin: a definite germination in the mind of an author, a set of historical events that triggered composition.

P-texts have collateral historical texts: an associated set of manuscripts, printers’ proofs, correspondence between the author and her agent and publisher.

P-texts have a reception history: post-publication reviews, first inclusions in anthologies and "canonizing" collections or series.

P-texts have publication histories: first editions, second editions, states, revisions, reissues, reproductions, republications, translations.

P-texts are prepared by professionals: authors, agents, editors, typesetters and layout specialists.

All of these things serve to make the transcription of a p-text into electronic form (e-text) by amateurs a much more difficult proposition than one would think when looking at the masses of e-text available today on the World Wide Web. Most of those e-texts, unfortunately, strip the p-text of its history, origin, collateral, reception and publication history, creating a dangerously unsound approximation of the original p-text, and leaving e-text transcribers open to charges, from more traditional scholars, that they are contributing to "the death of literature".

From P-Text To E-Text: Being An E-Text Transcriber

Sven Birkerts and other prophets of the "death of the book" aside, there is good reason for scholars and readers to applaud the proliferation of electronic literary texts (e-texts) on the World Wide Web. No only are such texts free to readers and scholars alike, but:

- e-texts offer transcribers (people who construct electronic literary texts) a rich toolset for annotating, explicating and enriching the texts on which they work in unobtrusive ways, providing cultural context for works that might otherwise be too dense for general readers

- the machine-readable format of such texts allows scholars to engage easily in various kinds of grammatical and lexical analyses that are difficult if not impossible to perform on printed texts (p-texts)

- the World Wide Web makes the work of transcribers immediately available to a worldwide community of readers and scholars, and circumvents the market mechanisms that keep many great works of literature either out-of-print completely or available only in expensive, hard-to-locate editions.

However, it’s not hard to see how Birkerts and others could get cultural heartburn looking at the textual junkyard that the WWW has become. In the case of electronic literary texts in particular, a number of critical failures on the part of e-text transcribers during the transcription and publication of their e-texts has left the nascent e-text industry open to all sorts of charges, some more serious than others, but all well-founded. Generally, these transcription failures can be classified as follows:

- The "a text is a text is a text" fallacy : most transcribers fail to provide any provenance whatsoever for their e-texts, as though all versions of, say, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, are textually and morally equivalent to one another. In many cases, a particular edition of a text is selected only because it is no longer governed by copyright laws: a criterion which is in and of itself irrelevant in selecting a reliable text to transcribe. In addition, many if not most literary texts changed over their publication life, both because they were revised by their authors and because the publication process itself introduces various kinds of errors and omissions into the text, and the documentation and comparison of these changes is an essential part of the e-text transcriber’s job.

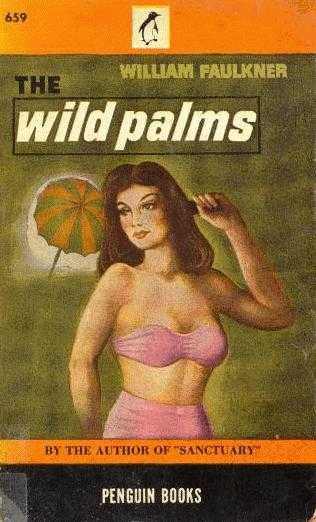

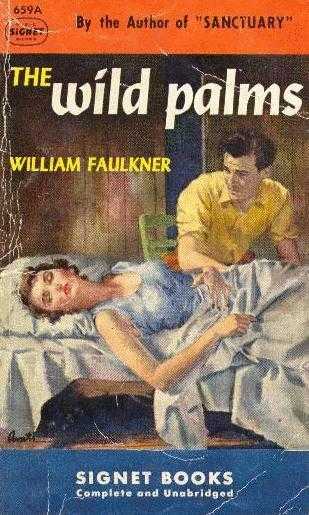

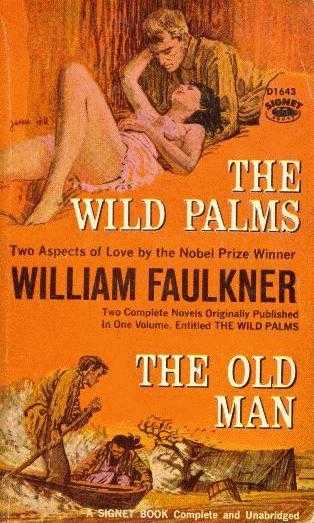

- The "the book is just a container" fallacy : many transcribers fail to provide any information on the format, binding, collation, state or issue of the text they are transcribing, stripping the text of its identity, and leaving the reader poorer in her knowledge of the text and her understanding of the form in which the text appeared before the public. Consider this illustration of the container fallacy from William Faulker’s corpus:

- The "format is irrelevant" fallacy : many transcribers fail to deal with the details of the format of the p-text with which they are working. Line breaks, pagination, running heads, page numbers and other aspects of the text can be significant, and require investigation before they are "stripped" from the p-text’s e-text version.

Three Paperback Editions of William Faulkner's The Wild Palms

This example clearly shows that the book is much more than a container for text: it is often the key indicator of the role, status and function of the text in a given social context at a given point in time. E-text transcribers must be sensitive to this sort of context, but most are not.

All of these errors speak clearly to me at least of the dominance, among e-text transcribers, of amateurs: people who love particular texts, and who want to see those texts either back in circulation or in circulation among a larger community in an easily-transmittable form, but who lack any training in the skills necessary to do a proper job of producing e-texts.

There is however no need for would-be e-text transcribers in enroll in a graduate English program. In a nutshell, the job of the e-text transcriber is no different than that of her comrade, the primary bibliographer: namely, the establishment of a reliable text with an appropriate and complete historical context. This two-pronged job -- the establishment of a reliable text, and the creation of an appropriate and complete context for that text – can be performed by any technically-competent person who takes the time to study the available resources on primary bibliography, and follows a few simple rules in transcribing, preparing and publishing electronic literary texts.

A Basic Model For E-Text Development

The preparation of an e-text from a p-text has four distinct phases:

- Selection of an edition from which to transcribe : the process of determining which version of which edition of a p-text the transcriber will use as the basis for her transcription, and which other versions of which editions of that p-text need to be compared against the transcribed version for variants and errors.

- Technical transcription of the text : the electro-mechanical process of rendering the p-text into machine-readable text.

- Preparation of the e-text : the editing and amendation of the machine-readable p-text and the creating of publishable forms of the e-text.

- Publication of the e-text : distribution of the e-text on the Web and in other media or formats.

Each of these areas requires that the e-text transcriber exercise her judgement, make transcription decisions, and document her rationale for those decisions.

P-Text Selection Guidelines

- Select a reliable text . Copyright is not the only reason for choosing a text, or even the most important reason. In the case of most of literature (roughly, literature published before 1920), the first edition of a work is always an historically interesting text to transcribe, and has some historical claims, but may be for a variety of reasons unreliable. Similarly, for 18th and 19th century authors, serial publication versions of the text are likely to be out of copyright, have historical claim, but are likely to have been reworked substantially prior to first book-form publication. It is always a good idea to check the primary bibliography of the author in question to determine which texts are generally reliable and which are generally unreliable, as well as to get other bibliographical information you’ll need during preparation.

- Document your selection, and your reasons for choosing the text you have chosen, and include that rationale in the transcriber’s notes that accompany your e-text . Reads and scholars using your text need to know which p-text the e-text is based on, and why you chose it. If you use a reprint, you need to provide both the bibliographical information on the reprint, and state which earlier version of the text it is a reprint of.

- Know the history of the text: both publication history and revision history . You need to make sure you understand (a) what editions of the text in question were published during and after the author’s life, and (b) what revisions were made (and by whom) during the p-text’s public life. If substantial revisions were made after the version of the text you are transcribing, you need to indicate that in your transcriber’s notes.

- Check national variances . Many texts differ across the Atlantic: the first US version of a 19th century British author, for example, stands a good chance of being an earlier version of the text than the first British edition, even when it was published later, since it was common to use the proof pages of first British editions (sent to New York via boat) to type-set first American editions; while the first British edition was revised before publication, the first American edition often was not.

Transcription Guidelines

- Beware of auto-correction . When you are scanning text, turn off the OCR software’s spelling correction software.

- Don’t correct an error silently . If you decide to correct an error in the text, that correction, along with the rationale for correcting the error, should be included in your transcriber’s notes.

- Don’t normalize house styles or national spellings . British -ise spellings should not be normalized to US -ize spellings, for example, nor should double-quotes be substituted for single quotes.

- Watch line breaks . In poetry, all line breaks are significant and should be retained. In prose, line breaks may be significant. Reproduce line-break dashes when they are significant.

- Retain all section breaks, chapter breaks, and part breaks . These are all significant in both poetry and prose; they represent authorial intent in most cases, and must be included for the text to be considered reliable.

- Normalize dingbats and em/en dashes appropriately . Use a standard ASCII representation for all dingbats used in the text. Reproduce em dashes as --, and en dashes as --.

- Normalize italics . Given the prevalence of HTML readers, it makes sense to mark italics in ASCII text versions using the HTML italics tags (<I>…</I>)

- When you cannot reproduce textual elements like diacritical marks or accents using ASCII text, note the loss of that information in the transcriber’s notes .

- Always reproduce the title page, dedication, epigram and other front matter . These are part of the text; they vary from edition to edition and version to version of the text, are significant, and represent authorial intent.

- Consider embedding page break information . It may be appropriate (particularly in HTML forms of the text) to embed information about page breaks and page sequencing. These can be added with <META> tags which will be ignored by the browser when viewing the document, but which can be extracted by any interested party by looking at the document’s source.

- Always reproduce all illustrations that accompany the text . Reproduce illustrations in the locations that they appear within the text of the p-text.

Preparation Guidelines

- Prepare multiple formats . Some audiences will want to read e-texts online, others will want to read offline, and still others will want to process e-texts using software of various sorts. If you produce HTML versions of the p-text, make them manageable in size for readers accessing them at lowwer modem speeds. If you produce ASCII text versions, consider avoiding introducing ASCII line breaks (CR-LF, or CONTROL-M); most text editors and readers will auto-wrap, and the absence of transcriber-introduced line breaks allows for smoother text processing. If you prepare the text in other formats (for example, Windows Help hypertext format) make sure you make appropriate software for reading available.

- Include all transcriber’s notes in every copy of the e-text . The transcriber’s notes should include information on the p-text, the tools used for transcription, the authoritative source of copies of the e-text, a summary of all changes you have made to the e-text (and your rationale for those changes) and information on all normalizations you have performed. Put this information in the ASCII version of the text, so that it remains with the text as the text is passed electronically.

- Annotate difficult content . Use the power of non-ASCII electronic media to annotate all the passages in the text in question that you feel may be difficult for a modern, non-specialist reader.

Publication Guidelines

-

Provide collation, publication data (number of copies in the run, publication date), and reception information with the versions of text. Though you shouldn’t embed these in the text itself, you should include these at the same site where you are publishing the e-texts: this kind of information is significant to scholars and serious, and can provide significant context for the casual reader. Also, if you can find contemporary reviews of the book, or letters by the author on the composition or publication of the edition you have transcribed, include those as well.

- Provide graphical specimens of the title page, the layout of the book, the dust wrapper and the book’s covers and spine with the versions of the text. Though you shouldn’t embed these in the text itself, you should include these at the same site where you are publishing the e-texts: this kind of information is significant to scholars and serious readers, and as the Faulkner example above illustrates, can provide significant context for the casual reader.

Putting These Guidelines Into Practice

Examples of all these practices can be found at my specimen site, Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford: The Collaborative Texts (http://www.noumenal.com/jcfmf/).

Coda: Why P-Texts Endure

Books are superior in every way but one to e-texts. That one flaw -- books cannot be processed, except serially, and by a human being -- alone warrants the existence of e-texts.

But only as ancillaries to books, not as substitutes. Books are far more interesting, and complex, than e-texts. They carry complex historical and cultural significance that e-texts cannot carry, and they carry these markings as well as their texts far better, far more cheaply, far more durably. and far more portably, than e-texts can (today at least).

Perhaps the best way to think of one's tasks is this: the e-text transcriber is not a revolutionary, doing away with the book in favor of a more trendy electronic substitute. Instead, the e-text transcriber should see herself as someone whose job it is to push the (narrow) margins of the electronic media with which she works to contain the full range and subtlety of the book as an historical form, and to preserve that complex significance in the transcription of the text from physical to electronic form. The establishment of a reliable e-text with an appropriate and complete historical context: that is the job of the e-text transcriber.

Otherwise, we are pretty much what Sven Birkerts and others suggest: shallow, mindless technocrats rampaging through the halls of culture and history, defacing our collective inheritance in the name of being cool. Hardly something worth doing...

Last updated on 06-22-97 by Marc Demarest (marc@noumenal.com)

The authoritative source of this document is http://www.noumenal.com/marc/etext.html